[ad_1]

Leslie Booker offers step-by-step instruction.

In the four foundations of mindfulness, as laid out in the famed Satiphatthana Sutta, the Buddha offers four postures for practicing meditation:

A monk knows, when he is walking,

“I am walking”;

he knows, when he is standing,

“I am standing”;

he knows, when he is sitting,

“I am sitting”;

he knows, when he is lying down,

“I am lying down”;

or just as his body is disposed

so he knows it.

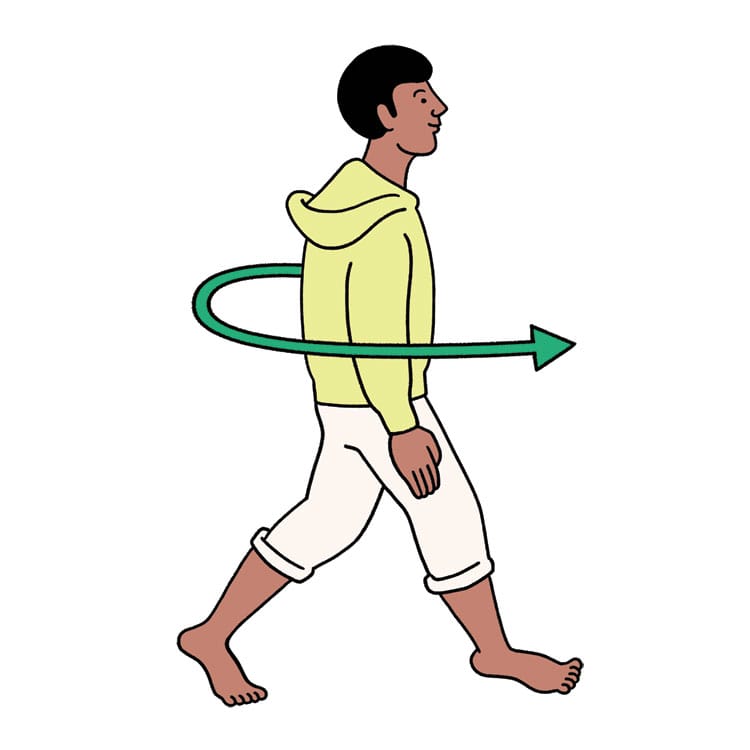

Walking meditation is often described as a meditation in motion.

In this practice, you place your full attention on the process of walking—from the shifting of the weight in your body to the mechanics of placing your foot. Walking meditation is an integral part of retreat life in many traditions and is used to offset and shift the energy of sitting practice. It is a bridge to integrate practice into daily life and can be more accessible than a sitting practice for many people.

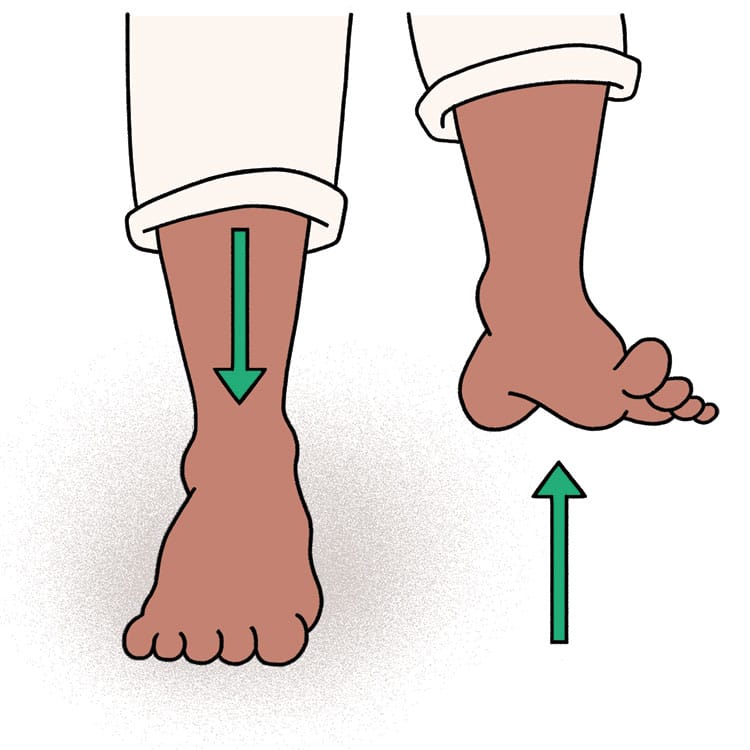

Find an unobstructed space where you can walk in a straight line for about ten feet. This short walking distance is the instruction given in the Theravada tradition. Others prefer to walk for greater distances. Bring your attention down to your feet and slowly shift your weight from side to side and front to back. Being in bare feet can bring more awareness to what needs to happen in the body to create balance.

Coming into physical stillness, lift the crown of your head up, slide your shoulders down and away from your ears, and lift your chest with dignity and pride, as if you were a king or a queen. You can clasp your hands behind your back, hold them in front of your body, or let your arms hang loosely to the side.

Lifting your right leg, notice the weight redistribution in your body. Place your attention on what the left side of your body needs to do to hold your full weight—spreading the toes, engaging the core. Extend the right leg forward, placing the heel on the ground and rolling onto the ball of the foot. As your weight shifts forward, notice how the heel of your left foot begins to lift. Swing the left leg forward and repeat.

Adding verbal cues is a great way to establish synchronization and rhythm within the body. As the mind begins to wander, use a simple verbal cue like “lifting, moving, placing” as a reminder to bring the mind back to the body. Incorporating a gatha, a short verse to support practice, is a common technique used in Thich Nhat Hanh’s communities. Here’s one that might be used for walking meditation:

(Breathing in) “I have arrived”; (Breathing out) “I am home.”

(Breathing in) “In the here”;

(Breathing out) “In the now.”

(Breathing in) “I am solid”;

(Breathing out) “I am free.”

(Breathing in) “In the ultimate”; (Breathing out) “I dwell.”

When you get to the end of your short walking path, come to a complete stop and take a breath. Turn a quarter of the way, maybe taking another breath, then fully turn all the way around, facing where you just came from. Start over with finding your posture and establishing your balance. Again lift, move, and place the foot.

At the beginning of this practice, you might notice that your steps are very calculated and robotic. See if you can begin to find more fluidity as you connect the breath with movement, perhaps letting go of the phrases and just allowing this to be a fully embodied practice. Start with about a ten-minute session, slowly building up to 30–45 minutes.

When you have come to the end of your practice, stand still, seeing where there is energy in the body and what is still. Notice what has risen to the top and what has been let go of.

[ad_2]

Source link