[ad_1]

LGBTQ+ adolescents are more likely than their heterosexual and cisgender peers to experience common mental health difficulties (Amos et al., 2020; Rogers & Taliaferro, 2020). A theoretical framework proposed to explain this is the minority stress theory, which suggests that LGBTQ+ individuals experience worse mental health as a response to chronic stress triggered by experiences of prejudice, identity concealment, and internalising queerphobia (Bränstörm, 2017; Weeks et al., 2023).

However, previous research in this area has many limitations. First, wellbeing is often used interchangeably with mental health when more precise frameworks of wellbeing have been proposed. The reviewed paper applied three different approaches to understanding wellbeing:

- The hedonic approach (also referred to as subjective wellbeing), comprising affect and life satisfaction.

- The eudaimonic approach, which emphasises a comprehensive psychological state, including optimism and self-esteem.

- The complete state approach, which focuses on the balance between wellness and distress.

Other weaknesses of this research area are that studies have more often focused on sexual orientation than gender identity, and studies on gender identity have frequently made binary comparisons of cisgender versus transgender individuals. Marquez and colleagues (2023) sought to address this by analysing data on sexuality and gender, as well as data on gender identity beyond the binary, in the context of these three wellbeing frameworks.

Previous research has highlighted inequalities in LGBTQ+ mental health, but less is known about comprehensive wellbeing inequalities (i.e., wellbeing defined and measured across its multiple domains, including positive affect, self-esteem, and life satisfaction).

Methods

The study used cross-sectional survey data from 37,978 adolescents drawn from the #BeeWell study – a cohort of 12-to-15-year-olds from 165 secondary schools in Greater Manchester. The authors estimated the difference in wellbeing according to each framework (hedonic, eudaimonic, complete state) between sexual minority groups and heterosexual adolescents as a reference, as well as disadvantaged gender groups and boys (including transgender boys) as a reference. They separately tested whether a gender modality (cisgender vs transgender) categorisation changed the results. Finally, they controlled for age/year group, eligibility for free school meals in the past 6 months, special educational needs (SEN), and ethnicity.

The authors estimated two structural correlated factors models (A and B) for each of the three different wellbeing frameworks (hedonic, eudaimonic, complete state). Model A included a gender identity variable (boy, girl, non-binary, other gender, prefer not to say gender), whereas Model B included a gender modality variable (cisgender vs transgender). In all the models, a disadvantaged group was compared to a reference group (e.g., gay/lesbian to heterosexual; SEN to no SEN; non-binary to boy; transgender to cisgender). These models were interpreted whereby wellbeing scores in an LGBTQ+ identity group were compared to that in a reference group.

Results

Sample characteristics

- The sample was made up of 51.5% Year 8 pupils (age 12-13) and 48.5% Year 10 pupils (age 14-15).

- With regards to gender, 41.7% of the sample identified as boys (including trans boys), 40% as girls (including trans girls), 2.4% as non-binary, 2.8% described themselves in another way, and 5.3% preferred not to say. Trans youth made up 7.1% of the sample.

- With regards to sexual identity, 2.7% identified as gay/lesbian, 7.7% as bi/pansexual, and 3.7% described themselves in another way.

- With regards to race and ethnicity, of all the adolescents, 18.1% were Asian, 5.5% Black, 0.8% Chinese, 5.9% mixed race, and 2.3% of other ethnicity.

- Finally, 14.2% had special educational needs and 25.4% were eligible for free school meals.

Main findings

All models demonstrated consistent inequalities in adolescent wellbeing across sexual and gender identities, when controlling for all the covariates:

- Compared to boys, non-binary adolescents, adolescents identifying with another gender, and adolescents preferring not to share their gender had lower wellbeing scores.

- Compared to heterosexual adolescents, bisexual/pansexual, gay/lesbian, adolescents identifying with another sexuality, and adolescents preferring not to share their sexuality had lower wellbeing scores.

- Compared to cisgender adolescents, transgender adolescents had lower wellbeing scores.

The comparison of gender identity categorisation to gender modality (cisgender vs transgender) categorisation revealed no substantial differences in the results. Finally, this pattern of results was consistent across the wellbeing frameworks of hedonic, eudaimonic and complete state wellbeing.

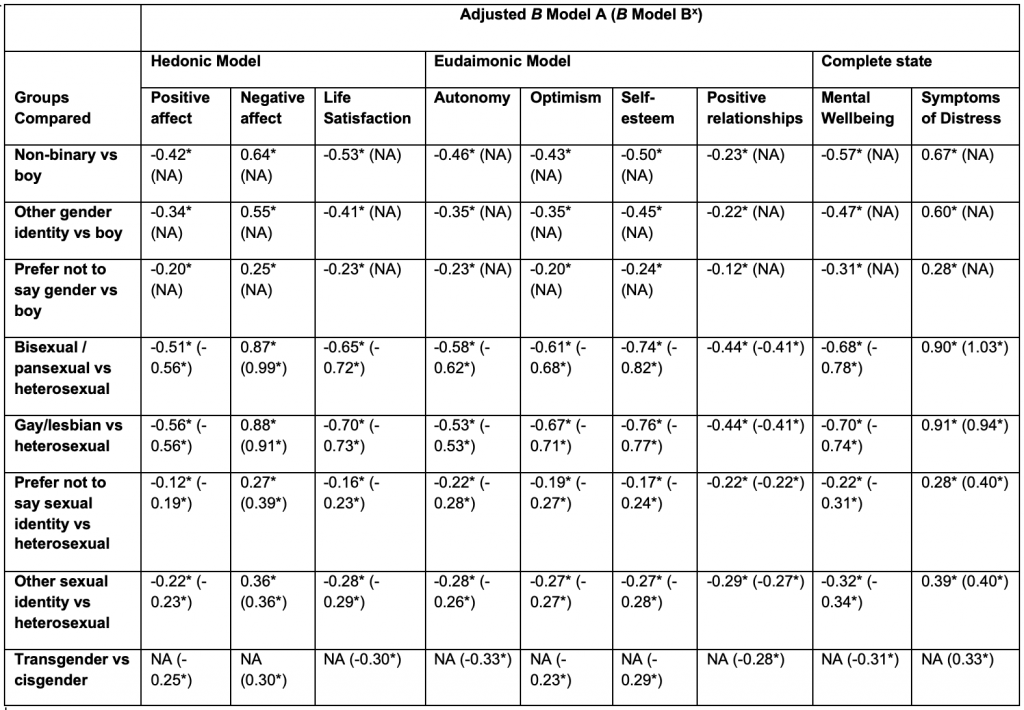

The largest gender inequality in all models concerned the difference between non-binary adolescents and boys (including trans boys). The largest sexual identity inequality in all models concerned the difference between gay/lesbian and heterosexual adolescents, but the difference between bisexual/pansexual and heterosexual adolescents followed closely behind in terms of effect sizes. See Table 1 for details and effect sizes.

Compared to inequalities pertaining to ethnicity, socio-economic disadvantage, age, and special educational needs, the inequalities concerning gender and sexual identity were greater.

Table 1. Adjusted Coefficients for Gender and Sexual Identities Predicting Wellbeing

Note: Adjusted B for categorical predictors represents the log of the odds ratio, which compares scores for individuals in one group to a reference group. x Model B refers to models where gender modality (cisgender vs transgender) was included as a variable in place of gender identity (boy, girl, non-binary, other gender, prefer not to say gender), which was used for Model A. * p < .001

Wellbeing scores were lower for LGBTQ+ adolescents across all different frameworks of wellbeing, when controlling for age, socio-economic status, special educational needs, and ethnicity.

Conclusions

Across different wellbeing frameworks, including subjective wellbeing (hedonic), psychological state wellbeing (eudaimonic) and complete state wellbeing, LGBTQ+ adolescents experienced worse outcomes than heterosexual and cisgender adolescents, even when controlling for age, socio-economic status, special educational needs, and ethnicity.

The inequalities concerning LGBTQ+ teenagers were greater than any inequalities related to these covariates. As such, improving the wellbeing and prevention of poor outcomes in LGBTQ+ adolescents should be prioritised within adolescent wellbeing interventions.

There is clear evidence of inequalities regarding sexuality and gender identity in early to middle adolescence and urgent interventions are needed.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This study has a large sample size that represents a major local authority in the UK and appears to match the socio-demographic characteristics on the national level, where comparison data is available, in terms of the gender and ethnic makeup. The #BeeWell study involves various school types, including mainstream schools, special schools, independent schools and more. Greater Manchester covers urban as well as suburban and rural areas, therefore the study is more generalisable to the national level of the UK. Another strength is the co-production of the study, as the surveys were co-created with 150 young people from 14 schools.

On a methodological level, the study improves on the past research on LGBTQ+ adolescents’ wellbeing by taking a comprehensive approach to wellbeing. Previous studies (see Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015) often focused on mental health symptoms, therefore tapping into the complete state framework of wellbeing, but did not explore the other theoretical frameworks of wellbeing in large samples, such as the hedonic and the eudaimonic approaches, which Marquez and colleagues did explore. These frameworks take into consideration aspects of wellbeing beyond symptoms of distress which are important for psychological development, resilience, and successful functioning (e.g., life satisfaction, self-esteem, positive relationships). Therefore, the current findings emphasise that LGBTQ+ adolescents’ inequalities in wellbeing pertain to a comprehensive range of wellbeing indices.

Limitations

With regards to the limitations, one weakness of the study is the cross-sectional data, which leaves us unable to conclude whether the inequalities are sustained across time. Its validity would be improved if wellbeing was investigated across two or more time points. The continuous funding and data collection for the #BeeWell study, however, shows promise for future research assessing the research questions of this paper in a longitudinal design.

Furthermore, the study does not investigate mechanisms behind the inequalities, therefore it is limited in supporting the minority stress theory and informing specific interventions to prevent the inequalities. As such, future research from the #BeeWell study (as well as other cohorts) should prioritise looking at large samples longitudinally to study causal pathways underlying LGBTQ+ wellbeing inequalities, such as factors mediating lower as well as greater wellbeing.

Finally, the current study assessed young people in early to middle adolescence, but levels of mental health difficulties continue to rise further into late adolescence (WHO, 2021) and many more adolescents might come out as LGBTQ+ at a slightly older age than 12 to 15 years old. As such, future studies should consider including adolescents across the developmental period.

This study has many strengths, including sample size and precision in measurement, but future research would benefit from a longitudinal approach and including older adolescents.

Implications for practice

Future research should assess the mechanisms underlying the LGBTQ+ adolescents’ wellbeing inequalities to explain what aspects of being LGBTQ+ contribute to poorer wellbeing, so that interventions can be designed to address these.

Knowledge on the mechanisms would allow policymakers and education practitioners alike to create practices that support LGBTQ+ teenagers on different levels. For example, if familial rejection and/or lack of support is an issue, then schools and community organisations could support parents in becoming better equipped to positively support their children coming out as LGBTQ+. An understanding of whether schools being inclusive and effective at preventing bullying of LGBTQ+ pupils could support funding for LGBTQ+ education, whether that be through ensuring more LGBTQ+ inclusivity in personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE) and other curricula, or building capacity of educational non-governmental organisations, such as Just Like Us to support more schools across the UK.

However, the fact that this paper does not uncover the mechanisms should not stop interventions from being put in place urgently, whilst more research is conducted.

Therefore, in the meantime, efforts should be made to make schools more inclusive, such as the aforementioned inclusive education practices and funding of organisations such as Just Like Us. Another worthwhile approach to address these inequalities would be efforts to train teachers, both new and old, to be equipped to support LGBTQ+ students in a pastoral capacity.

When I was a queer secondary school pupil in Essex in the early 2010s, I do not recall speaking to any teachers about mine, their, or anyone else’s LGBTQ+ identity. Identity being a taboo made me feel like this was a part of me that was not appropriate, therefore shameful. It also meant that I did not feel comfortable to raise homophobic bullying up with any teachers. The teachers need to be informed about LGBTQ+ identities and the difficulties faced by LGBTQ+ young people, such as microaggressions, gender dysphoria, transphobia in the media, or unavailability of gender affirming care for most under-18s in the NHS.

Additionally, psychological support in Child and Adolescent Mental Health services should be LGBTQ+ inclusive and available within reasonable wait times. Like many other young people, I was not able to access LGBTQ+ affirmative therapy until my 20s and I am sure that I would have needed less support had it been provided in the earlier stages of my wellbeing declining.

Large scale research needs to investigate mechanisms underlying LGBTQ+ wellbeing inequalities, but in the meantime, we should already be intervening to support LGBTQ+ adolescents in schools and in mental health services.

Statement of interests

I have in the past volunteered with the charity that I mention in the implications of this research: Just Like Us.

Just Like Us offers support and talks to secondary schools exclusively on LGBTQ+ inclusivity and growing up LGBTQ+, therefore I believe its activity at a large scale is indispensable for addressing the LGBTQ+ adolescents’ wellbeing inequalities. I use it as an example of an organisation, however any organisation with similar missions and services should be supported in the efforts to address this issue.

Links

Primary paper

Marquez, J., Humphrey, N., Black, L., Cutts, M., & Khanna, D. (2023). Gender and sexual identity-based inequalities in adolescent wellbeing: findings from the #BeeWell Study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2211.

Other references

Amos, R., Manalastas, E. J., White, R., Bos, H., & Patalay, P. (2020). Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: a contemporary national cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 36-45.

Bränström, R. (2017). Minority stress factors as mediators of sexual orientation disparities in mental health treatment: a longitudinal population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health.

Just Like Us. (n.d.). Who We Are. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

Mental health of adolescents. (2021, November 17). World Health Organisation.

Plöderl, M., & Tremblay, P. (2015). Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(5), 367-385.

Rogers, M. L., & Taliaferro, L. A. (2020). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among sexual and gender minority youth: a systematic review of recent research. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12, 335-350.

Weeks, S. N., Renshaw, T. L., & Vinal, S. A. (2023). Minority stress as a multidimensional predictor of LGB+ adolescents’ mental health outcomes. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(5), 938-962.

Photo credits

[ad_2]

Source link